CULTIVATING FLAVOR: Farming and the Roots of Flavor

Flavorful ingredients form the foundation of great cooking. And much of the flavor of cultivated ingredients is determined by what happens on the farm. In the same way that every decision a cook makes—from ingredient selection to method of preparation, to gauging the ideal moment for serving—determines the quality of a dish, the flavor of produce, meat, and dairy will get either enhanced or diminished by each step a farmer takes in raising, harvesting, and handling crops and animals.

A farmer's choices regarding management of the land, selection of crop varieties and livestock breeds, and proximity to market are crucial determinants of flavor. Guiding those choices are a farmer's observational skills, experience, and knowledge of the farm, as are customer feedback and expectations. While no one agricultural system can guarantee better flavor, small-scale, ecologically managed, diversified farms that sell to local markets have certain significant flavor advantages over long-distance, industrialized agriculture.

Read More...

Industrialized agriculture is built around the centralization and specialization of food production. In that system, decisions about variety and breed selection, fertilizing and feeding practices, and harvest time are made with the goals of fast growth, high yield, and long shelf life. The distance between grower and customer provides little incentive for a farmer to focus on flavor, and the volume demands of the giant food retailers and processors favor severe limitation of the range of crop varieties and breeds that are used. For example, there are thousands of apple varieties, but only a dozen varieties account for fully 90 percent of the apples sold through major U.S. supermarkets. Rather than offering the depth and range of flavor that nature provides, most supermarkets sell fruit that was picked too early, greens that are too long from harvest, and bland meat and dairy products that have unnaturally uniform flavors from coast to coast and from season to season.

Industrialized agriculture is built around the centralization and specialization of food production. In that system, decisions about variety and breed selection, fertilizing and feeding practices, and harvest time are made with the goals of fast growth, high yield, and long shelf life. The distance between grower and customer provides little incentive for a farmer to focus on flavor, and the volume demands of the giant food retailers and processors favor severe limitation of the range of crop varieties and breeds that are used. For example, there are thousands of apple varieties, but only a dozen varieties account for fully 90 percent of the apples sold through major U.S. supermarkets. Rather than offering the depth and range of flavor that nature provides, most supermarkets sell fruit that was picked too early, greens that are too long from harvest, and bland meat and dairy products that have unnaturally uniform flavors from coast to coast and from season to season.

Farmers who engage in small-scale, local agriculture have the advantage—and the challenge—of direct accountability to the end customer. In that local market, flavor is the key to customer loyalty and repeat sales. That flavor is achieved in several ways, as follows.

- The scale of farming and of the market allows for the planting of a large number of different crops and a wide selection of crop varieties based on flavor.

- Unlike the hit-or-miss quality of planting large acreage in a single crop, planting a wide selection of crops means that in any given year, there are likely to be a number of crops for which the weather conditions are right for producing great flavor.

- Proximity to market enables farmers to pick fruit when it is either just ripe or near ripe and to get vegetables to market within hours of being picked.

- The need of steady supplies of produce for weekly farmers markets encourages staggered planting and harvesting, which ensures freshness on an ongoing basis.

- Direct sales give farmers greater control over the handling of their products, which can help minimize flavor loss due to mishandling.

- Direct sales facilitate conversations with customers whereby farmers can communicate information about cooking and handling, and customers can provide valuable feedback about quality.

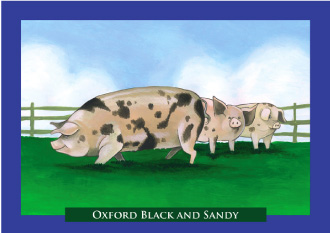

On the subject of how important varietal selection, ripeness, and freshness are to the flavor of produce, there is little disagreement between ecologically minded farmers and farmers who use conventional farming practices. Disagreement arises over the effect that farming practices exert on flavor. In language and philosophy, industrialized agriculture takes the perspective that nature is insufficient, having neither the capacity nor the wisdom to provide. In contrast, ecologically minded farmers look directly to nature for information and inspiration on how to manage their crops and livestock. For the latter, the sources of nutrients and the methods by which plants or animals access them are crucial to flavor development. Because soluble chemical fertilizers are designed for plants to take them up easily, those fertilizers bypass the slower and more complex natural systems, by which plants access nutrients in the wild. To ecologically minded growers, that bypass diminishes the potential for flavor by favoring rapid growth—based on a limited range of minerals—instead of favoring slower growth and access to a wider range of minerals, which provides the time and materials to build flavor complexity. The same is true for livestock, poultry, and dairy products when—rather than promoting fast growth rate and high yield via confinement, drugs, and unnatural diets—ecological farmers choose breeds with good grazing and foraging abilities and then allow their animals to seek out the plants and insects that are parts of their natural diets. The goals are well-managed animals and pastures producing meat and dairy products with rich, complex flavors that change with the breeds and with the seasons.

In exploring the connection between farming practices and flavor, I've talked with many farmers about what they know—and what they believe—to be influencing flavor on the farm. When asked about the roots of flavor, ecologically minded farmers often begin with specific ideas about the factors that contribute to flavor quality. As the conversations continue, however, they keep adding to their lists of influences; and their lengthier lists of factors reflect the complex nature of flavor production.

On Flavor Notes—under the category Cultivating Flavor—I will be posting notes from my conversations with farmers. And I invite you to add—in the Comments section—your own observations and thoughts about flavor.

Read more about farming and flavor on Flavor Notes.

Read more about farming and flavor on Flavor Notes.

Read more about farming and flavor on Flavor Notes.

Read more about farming and flavor on Flavor Notes.

Industrialized agriculture is built around the centralization and specialization of food production. In that system, decisions about variety and breed selection, fertilizing and feeding practices, and harvest time are made with the goals of fast growth, high yield, and long shelf life. The distance between grower and customer provides little incentive for a farmer to focus on flavor, and the volume demands of the giant food retailers and processors favor severe limitation of the range of crop varieties and breeds that are used. For example, there are thousands of apple varieties, but only a dozen varieties account for fully 90 percent of the apples sold through major U.S. supermarkets. Rather than offering the depth and range of flavor that nature provides, most supermarkets sell fruit that was picked too early, greens that are too long from harvest, and bland meat and dairy products that have unnaturally uniform flavors from coast to coast and from season to season.

Industrialized agriculture is built around the centralization and specialization of food production. In that system, decisions about variety and breed selection, fertilizing and feeding practices, and harvest time are made with the goals of fast growth, high yield, and long shelf life. The distance between grower and customer provides little incentive for a farmer to focus on flavor, and the volume demands of the giant food retailers and processors favor severe limitation of the range of crop varieties and breeds that are used. For example, there are thousands of apple varieties, but only a dozen varieties account for fully 90 percent of the apples sold through major U.S. supermarkets. Rather than offering the depth and range of flavor that nature provides, most supermarkets sell fruit that was picked too early, greens that are too long from harvest, and bland meat and dairy products that have unnaturally uniform flavors from coast to coast and from season to season.